02 December 2020

A No Deal Brexit will increase fruit and vegetable prices on 1st January 2021

In this blog we analyse the likely impacts of the UK’s departure from the EU on fruit and veg prices in the UK. Preliminary analysis from the SHEFS consortium shows that the new trade tariffs that will apply as a result of a “No Deal Brexit” would increase the price of fruit and veg in the UK and make it even more expensive for families to purchase a healthy diet.

A “No Deal Brexit” will result in an increase in fruit and veg prices

Preliminary analysis from ongoing research has revealed that a No Deal Brexit would increase prices of fruit and veg in the UK. The UK is highly reliant on fruit and vegetable imports, currently importing 65% of total UK supply. In the event of a No Deal Brexit, imports from the EU would automatically be subject to new UK ‘Most-favoured Nation’ tariffs. In addition, imports from non-EU countries may also be subject to increased tariffs. As a member of the EU, the UK benefitted from around 40 free trade agreements signed by the EU. The UK has so far signed bilateral deals replicating just 22 of these agreements.

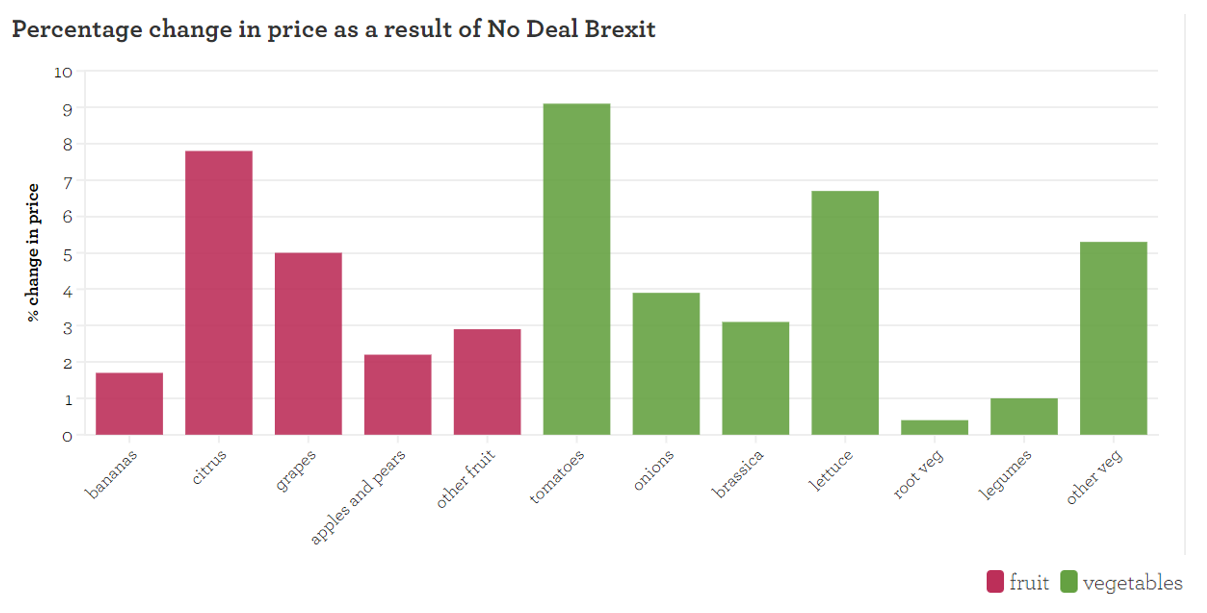

If tariff increases are passed directly on to UK citizens, the average British family would pay 4% more for their fruit and vegetables from 1st January 2021 (compared with only a 0.6% increase that would occur under an EU Free Trade Agreement (FTA)). Prices for some products could rise by even more: for example, tomatoes would become 9% more expensive. For a family of four (two adults and two children), this would mean an increase of £25-28 a year (depending on the children’s age) to their fruit and vegetable bill. If families increased their consumption to the recommended five-a-day this would cost £65 per year more for a family of four under a No Deal scenario. Other food categories would also be subject to increased tariffs in a No Deal Brexit scenario, further driving up household grocery bills.

How was this calculated?

Researchers from the Wellcome-Trust funded Sustainable and Healthy Food Systems (SHEFS) research consortium led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and from Imperial College London used 2019 import data from HMRC to identify imports of 12 popular fruit and veg categories from the EU and non-EU countries. They then applied the government’s new UK Global Tariff (the UK’s ‘Most-favoured Nation’ tariff), which will apply to EU produce in the case of a ‘no deal’ Brexit, to each fruit and veg subcategory to calculate the impact on price of the new tariffs compared to the current UK fruit and vegetable import tariffs. While it is hard to assess how the new tariffs might filter through to consumers and the extent to which they will be reflected in retail prices, the findings suggest that even without any other Brexit related changes to the UK’s supply chain or exchange rates, a no deal scenario could have a significant impact on prices, with other food categories also likely to be affected. The British Retail Consortium suggest that a deal with the EU would be in the best interest of consumers as retailers would find it impossible to change sourcing before January 2021 in a No Deal scenario to avoid passing on increased prices to consumers. (These preliminary results reflect the potential impact of import tariffs on fruit and veg prices after a no deal Brexit. Potential extra costs that are not taken into account in the analysis, such as transaction costs due to border checks, could further exacerbate the estimated effect.)

Beyond the effect of tariffs, Brexit also poses a range of other challenges to fruit and veg supply chains…

The food industry has been warning of the potential for additional costs and significant delays at UK borders e.g. for customs and plant health checks, and a lack of cold storage capacity in the UK, and the potential for shortages and concomitant food prices rises. These issues will particularly have an effect on perishable food products, including fruit and vegetables. There has been much debate over whether after Brexit it will be possible to import foods produced to lower standards than those produced in the UK as a result of new free trade agreements.

Why does this matter?

We all know that fruit and veg are an essential part of a healthy diet, and we should be eating more to protect ourselves from diseases such as obesity and some cancers. However, in the UK F&V consumption is far below the recommended level of at least 5 portions a day needed to help prevent disease and promote health. The average adult eats just under four portions a day, and teenagers consume even less. There is also a big difference between income groups with the highest income groups eating one and a half more portions per day than the lowest. There is an important need to drive up consumption to meet these recommendations.

Food prices are a major driver of food choices and increases in prices are therefore likely to reduce fruit and veg consumption, further damaging the health of the nation and making it harder for the Prime Minister to deliver on the ambition in his obesity strategy. Even before the pandemic, many people struggled to afford a healthy diet. For many the situation is likely to have deteriorated since people have being feeling the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic with Universal Credit applications skyrocketing and many others experiencing reductions in income.

We need to invest in UK horticulture…

The UK is heavily reliant on EU imports for the majority of the fruit and veg we consume. The UK produced 3.1 million tonnes of fruit and veg last year – a quarter of what the UK population needs to meet Eatwell Guide recommendations.

There is a strong case for the Government to invest in horticulture to increase production of those fruits and veg that grow well here. If accompanied by policies to drive up consumption, this would benefit our economy, our health, and increase the resilience of our fruit and veg supply chain to potential trade disruptions like that posed by a no deal Brexit or climate shocks overseas.

With the British climate more conducive to vegetable production than for example, many tropical and citrus fruits, there is an opportunity to invest in Britain’s efficient yet historically underfunded vegetable horticulture sector. Despite producing just over half of our total veg supply, the quantity of land used to grow our veg takes up less than 1% of total agricultural land area in the UK. For the population to eat 3.5 portions of veg a day at current yields and domestic production ratio, another 115,789 hectares of land would need to come into production, bringing the overall amount of land required to just 1.4% of total agricultural land available.

On 30th November 2020, Secretary of State George Eustice outlined the Government’s new ‘Path to Sustainable Farming’. He said: “We need to design a policy that is not only right for those that are the custodians of the countryside today, but is also right for those who will follow in their footsteps tomorrow.” As part of this a new Environmental Land Management Scheme will be introduced which will reward farmers for good environmental practice, including preventing floods, planting trees, and committing to higher standards of animal welfare. With ministers describing the new system as the most fundamental shift in farming policy for 50 years, and a National Pilot of the scheme due to commence in 2021, now would be an opportune moment to invest in British fruit and veg production.