16 February 2022

Food Prices Tracking: February Update

by Shona Goudie and Indu Gurung

Food price inflation over recent months is an area of growing concern. In this update we look at what has happened to food prices in the past month and what we might expect to happen next.

What has happened over the past month?

Overall Inflation in the UK

New Consumer Price Index (CPI) data published today shows that overall inflation in the UK rose by 5.5% in the 12 months to January 2022, up from 5.4% in December 2021. This is the highest 12-month inflation rate seen in the National Statistic Series, which began in January 19971. The Bank of England have revised their predictions again with overall inflation now estimated to rise to as high as 7.25% by April2.

UK Food Prices

The CPI data charting take-home retail prices for commonly purchased food and drink items shows that prices have risen 4.3% in the 12 months to January 2022. Prices rose across all the food categories monitored, with oils and fats seeing the largest rise of 15.9%. Other food categories continue to rise with fruits now 6.9% higher; vegetables 4.5% higher; milk, cheese and eggs 5.7% higher; and meat 3.9% higher.

Other measures of food inflation also show that food prices are rising. In January 2022, the BRC-NielsenIQ price index shows food inflation was 2.7%, up from 2.4% in December 20213. (This was notably three times as high as non-food inflation which was at 0.9%). Kantar’s measure of food inflation similarly shows an increase, from 3.5% in December to 3.8% in January4. According to Tesco their food price inflation over the past three months has been approximately 1%, and they have disputed claims that the cost of basic staples is increasing more than other products5.

Predictions are that food prices in the UK will continue to rise through 20226 with Tesco warning that “the worst is yet to come” and that average prices could increase by as much as 5% in supermarkets5. Similarly, Kantar predict that annual food bills will rise by £180 on average7.

Global Food Prices

The FAO’s food price index, which tracks global food prices for key food commodities, averaged 135.7 points in January 2022, 1.5 points (1.1%) higher than in December 2021. The increase has mainly been driven by oils and dairy. Wheat prices which had been rising considerably have started to stabilise following large harvests in Australia and Argentina9. Global food price rises continue to be driven by labour shortages, extreme weather impacting on harvests, and high input and energy costs8, and FAO’s global projections suggest that food prices are likely to remain high in 2022.

Impact of inflation on low-income households

Average inflation is not entirely indicative of the potential impact of price rises on low-income households, as it masks variation across product ranges - for example, cheaper product ranges could be subject to higher inflation. It also masks variation in inflation rates across different food categories so does not show if healthy food is more likely to increase in price.

Jack Monroe, food poverty campaigner, has successfully brought attention in recent weeks to the lack of Government data on inflation rates for the cheapest basic ranges of food10 prompting the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to announce plans to make improvements11. The ONS subsequently reported that lower income households have not been worse hit by overall inflation12. They say this is because higher income families spend a larger proportion of their income on petrol, which is the area where prices have increased most. However, they didn’t specifically comment on whether food inflation is disproportionately affecting low-income households. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) argue that because low-income households spend a higher proportion of their income on food and fuel that they are hit the hardest13. Using proportion of expenditure spent on food is a limited measure where assessing food insecurity as lower expenditure on food could be indicative of households cutting back on food spending rather than them having sufficient money for food.

Cost of living

The ability to afford food is impacted by a household’s overall available budget. As covered in our previous blog, the cost of living crisis will put increasing pressure on the ability of many UK families to afford the food they need, with a number of changes in April meaning that the cost of living will rise overnight (see here for our previous blog on the implications of the cost of living crisis on food). Food is often considered to be a “discretionary purchase” - i.e. an area that people can cut down on when their budget it tight - unlike energy bills which are harder to restrict. People may switch to cheaper products which are more likely to be unhealthy, or cut back on the amount of food they buy altogether and go hungry. New Food Foundation data shows food insecurity levels are already rising14, and food banks are reporting overwhelming demand15. Furthermore, food banks are also being hit by increasing energy prices and running costs16.

At the start of February, it was confirmed that as predicted the energy price cap will be increasing drastically by 54% in April, costing the average household an extra £693 per year. Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, responded by announcing support measures for low-income households including £200 off energy bills - but not until October and this must be paid back over the following five years. There will also be a council tax rebate of £150 for bands A-D that does not have to be repaid17.

While these measures are welcome, they are insufficient to counteract the impact of the increases that will be seen in April. Families are already struggling from the cap increasing in October 2021 by £139 on average, putting a strain on their budgets. The new increase is approximately five times as high and will likely have a much more severe impact. The NIESR predict that destitution could increase by 30% in the next year due to inflation, higher bills and taxes18.

What’s more, the government have announced the introduction of measures so that people claiming Universal Credit will have less time to find a job before sanctions. This is also highly likely to increase food insecurity and food bank use19,20. Food insecurity levels in benefit recipients are already disproportionately high - our newest data shows that people on Universal Credit have been five times as likely to experience food insecurity over the past six months compared with people who aren’t on Universal Credit21.

What can we learn about the impact on food purchases from the Credit Crunch?

The Credit Crunch of 2008 was a worldwide economic crisis which saw overall inflation increase, wages decline and unemployment rise, putting a huge strain on households’ finances and disposable income. At the same time, there was a sharp rise in food prices - increasing by 10% more than all other goods between 2007 and 201222. This was in part due to increases in global food prices, but the UK was worse affected than many other comparable countries. So, what can we predict about how the 2022 cost of living crisis, increasing inflation and increasing food prices will affect food purchases by families based on what happened in 2008?

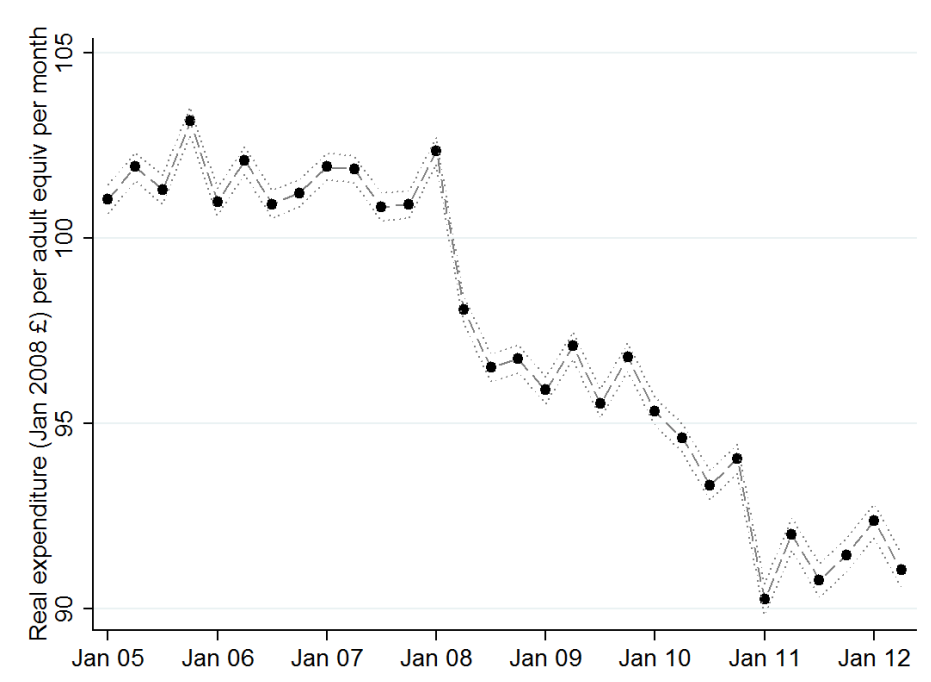

Food is often considered to be a “squeezable” part of people’s expenditure. This is what happened in the credit crunch when families faced lower incomes and higher costs. In real terms, average expenditure on food decreased:

Source: Institute of Fiscal Studies

The way that people managed to reduce their expenditure was by buying fewer and cheaper calories. While buying fewer calories could be argued to be a positive given that two thirds of the population are living with overweight or obesity and therefore consuming too many calories, it is still essential to ensure a healthy nutritional intake when losing weight. The problem is that people switched to cheaper foods24 which tend to be calorie-dense, nutrient-poor foods (i.e. lacking in vitamins, minerals and fibre that are essential for health). For example, on average healthier foods such as fruit and vegetables are three times more expensive per calorie than less healthy foods25.

The evidence shows that most of the increase in calorie density was due to changing the types of food purchased rather than switching to a more calorie dense version of the same food with people switching to foods of poorer nutritional quality: families bought less fruit and vegetables, and more processed sweet and savoury food26. Not only is decreasing fruit and veg concerning for health, but there is an increasing evidence base showing that highly processed foods eaten in large quantities are damaging to our health.

Food purchases by households with children were more affected by the recession than other household types, reducing the number of calories they were buying more than other households and having a bigger decline in nutritional quality of food purchased27. This is particularly of concern given that we know that households with children already have higher levels of food insecurity28 and that levels of childhood obesity have increased dramatically over the course of the pandemic.

Source: Children's Right2Food Dashboard

The reduction in nutritional quality of food purchased during the financial crisis of 2008 could reasonably be expected to be repeated during the cost of living crisis in 2022. Given that low-income families are likely to be more affected by financial strain, this could further exacerbate pre-existing dietary inequalities. The measures announced by Government this month are not sufficient to protect people from food insecurity and ensure everyone can afford enough nutritious food, especially groups that are known to be at risk of food insecurity such as households with children and households receiving Universal Credit. As food prices and the cost of living continue to rise, levels of food insecurity are highly like to continue to increase in the absence of further measures.

For more information on food prices, see our Food Price Tracker.

The next update will be published on 23rd March.

Shona joined The Food Foundation as a Project Officer in 2019 and has worked on research, policy and advocacy across a range of projects over that time including leading our food insecurity surveys and flagship annual Broken Plate reports. She now works across the charity's policy portfolio including our children's food campaigns, food insecurity and food environments. She is a Registered Associate Nutritionist with a background in clinical nutrition who worked in dietetic departments in NHS hospitals before joining The Food Foundation.

Indu joined The Food Foundation in 2019 as part of the Rank Foundation’s Time to Shine scheme, moving into a Project Officer role in 2020. She works on the Peas Please and Plating up Progress projects. Prior to joining The Food Foundation, Indu completed a MSc in Public Health and a BSc in Human Nutrition. She is interested in reducing health inequalities, children’s health and wellbeing, and sustainable and nutritious food system/diets. Indu is also a lover of veg, having recently taken up urban gardening.