Commonwealth Food Futures 2022

The Food Foundation hosted a Commonwealth Food Futures 2022 event in July, which coincided with the Birmingham Commonwealth Games.

The Food Foundation brought city leaders from around the world together for a special event, coinciding with the Birmingham Commonwealth Games, to share ways to transform the food system.

Introducing Commonwealth Food Futures 2022

Podcast

What we delivered

We brought distinguished speakers from 20 cities around the world together to showcase their plans to transform the food system, including Dr David Nabarro, co-leader of the United Nation's Global Crisis Response Group and Foreign Commonwealth and Development Minister Amanda Milling.

Key highlights included

The event was headlined by Dr David Nabarro CBE, part of the United Nation's Global Crisis Response Group and the World Health Organisation's Special Envoy on Covid-19, who spelled out the critical need for food policy to be included in mainstream urban planning amid the climate crisis and dual burden of obesity and undernutrition.

Foreign Commonwealth and Development Minister Amanda Milling affirmed a £1.5 billion government funding commitment to improve global nutrition. Speaking during the event, said the funding would be put in place by 2030 for "interventions to improve nutrition right across our aid work".

Thirty people from cities around the world also signed the Birmingham Food Justice Pledge, a formal commitment ensuring all citizens - irrespective of status - are entitled to safe, nutritious, and sustainable food. The signatories included top officials from cities in India, Bangladesh, Namibia, Malawi, Kenya and South Africa.

The event also provided a platform to highlight the Birmingham Food System Strategy, an eight-year project to create a food system and economy where food choices are affordable, nutritious and desirable for all citizens. It is currently out for public consultation.

Many of those attending have already signed up to our Food Cities 2022 Learning Platform for cities as part of a commitment to transforming their food system.

Video analysis of the sessions

Highlights from day one

Reflections as the first day concludes

India's leading role in transforming food systems

How will Commonwealth Food Futures benefit Birmingham?

What city leaders said about the event

World Health Organisation Special Envoy David Nabarro on sustainable food futures

This article was written by David Nabarro in advance of the Commonwealth Food Futures 2022 event

"In 2015, world leaders agreed on an ambitious plan to make the world a truly sustainable, equitable, resilient place for everyone that inhabits it by 2030 - with no-one being left behind.

"This plan, also known as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, is a universal call for all to work together to end poverty and hunger, to protect our planet, and to enable everyone to have opportunities for living, working and happiness.

"The plan has 17 interconnected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that set the standard for harmony among economic, social, and environmental influences on both people and the planet.

"With 2030 just eight years away, how are we doing? In May 2022, the United Nations Secretary-General released his annual SDG scorecard where he highlighted the challenges to the SDGs resulting from several interlinked shocks facing the people of our world.

"These include the Covid-19 pandemic, rapidly accelerating climate change, and increasing conflict, including the war in Ukraine.

"The Secretary-General’s Global Crisis Response Group (GCRG), set up in March 2022, describes how these shocks have led to higher prices for food, energy and fertiliser, triggering the 'largest cost-of-living crisis in a generation'.

"No country or community is left untouched. Low-and middle-income countries are the most affected, but even poorer people in high-income countries, such as the United Kingdom, are experiencing deeper hardship too.

"The cost of living crisis is everyone's problem, and we are all called on to find effective responses.

"This is why I enjoy working on food. Food defines us as individuals and links us together as families and communities, cities and nations.

"Food underpins our culture, our economy, and our relationship with the natural world. Food connects to all of the 17 SDGs.

"The world's food systems touch every aspect of human existence - making them not just essential for human life but also vital as potential instruments of change.

"A concerted science-based effort is required to ensure that food is good for people, for nature, for the environment and for the climate.

"Ensuring that it is equally good for farmers and food processers, and especially so for smallholders, women, indigenous people and young people, indeed for everyone, will lead to the achievement of the SDGs and better lives for all, now and in coming generations. Without it, the SDGs cannot be achieved.

"Today’s food production and processing systems are under more pressure than ever. Many are beset by challenges: they are not sustainable and damage environments.

"We have seen during Covid how they are brittle and easily disrupted and need to be more resilient. Numbers of people with non-communicable diseases (coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, and conditions related to obesity), are increasing exponentially, especially in poorer communities, with significant impacts on health care costs everywhere.

"We see huge inequalities in people’s abilities to maintain good nutrition through what they eat: the costs, to societies, of the impacts of poor diets on people’s health food are huge.

"In 2021 United Nations Food Systems Summit sought to energise and accelerate the collective journey to eliminate hunger, boost nutrition, create more inclusive and healthier food systems and safeguard the health of our planet - ultimately to deliver progress on all SDG’s.

"The UN Secretary-General called for concerted action by all citizens to radically change the ways in which food is produced, processed, and consumed.

"Critically, he recognised that transformations within complex systems, such as the food system, require a different way of reaching out to and connecting with stakeholders.

"To this end, he invited all stakeholders, many with differing perspectives on how these challenges are best analysed and tackled, to convene multi-stakeholder dialogues.

"These dialogues were a means to identify the most powerful ways to make our food systems sustainable, more equitable, but importantly, and as this ongoing multi-crisis has spotlighted, the need to make them a lot more resilient from disease, climate change, conflict, and other shocks.

"My experience is that multi-stakeholder dialogue can increase trust amongst stakeholders which in turn provides the conditions for greater alignment and systemic action.

"The objective with the Food Systems Summit Dialogues was to highlight, not only what matters to a wide range of stakeholders, but critically to highlight a potential solution space that the stakeholders might be prepared to adopt.

"These dialogues contribute towards greater convergence on the means to pursue systems transformations and increase the likelihood for cooperative action towards achieving agreed outcomes.

"The Food Systems Summit Dialogues have created profound engagement on an enormous, and unprecedented scale around the ways that food systems do and do not work for people and planet.

"Dialogues were organised independently; others were organized by national governments who nominated National Dialogue Convenors. Many were organised by cities too. Altogether over 1,600 dialogues took place, bringing together almost 110,000 people.

"In 117 countries the dialogues led to national food systems transformation pathways which are publicly posted and set out what needs to happen, who needs to be involved and when results are expected.

"They reiterate that for truly transformative change, outcomes must be inclusive, respectful and people centred.

"Cities are on the frontline of responding to many of the crises being faced by humanity. They make critical contributions to sustainable development.

"Yet Covid-19 and other shocks have highlighted how many local authorities, and city governments, are not yet fully able to respond meaningfully to these challenges.

"Despite an increasing understanding of the important role of food systems in urban environments, for many cities, food is still not yet part of mainstream urban planning, at least not within the bounds of devolved powers.

"Case studies from Birmingham and Pune, and others in the Food Cities 2022 Partnership, highlight the dividends for the citizens of both cities from being more intentional about their city food strategies, as contributors to sustainability, equity, and resilience.

"Some cities have gone far, becoming catalysts for national food systems transformation.

"Today’s shocks provide an impetus for tackling structural and institutional challenges related to urban food policy and an opportunity for catalysing change.

"The Food Systems Summit highlighted the potential of multi-stakeholder dialogue as a tool that decision-makers can use to encourage the emergence of city food strategies that work better for people, and for the planet, contributing to the vital universal ambition of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the SDGs.

David Nabarro is co-lead of the Food Workstream of the Secretary-General’s Global Crisis Response Group (GCRG), Special Envoy of the WHO Director-General on COVID-19. His social enterprise 4SD designed and developed the methodology for the Food Systems Summit Dialogues.

Blogs from conference participants

Sukhwinder Singh, designated officer Food Safety Administration in the Punjabi capital of Chandigarh in Northern India, is involved in the Eat Well India initiative, a major project to transform food systems to provide safe, healthy and sustainable food in the face of climate change – an ambition shared by all The Food Foundation's Food Cities.

"I look after the food safety administration of all food being produced, industrialised, sold and ultimately consumed, as well as enforcing provisions of the law here. Safe foods and good healthy diets are vital. India has a high burden of food borne disease, under-nutrition and micronutrient deficiency.

"Our ambition is to build a sustainable, ethical and nutritious food system and a thriving local economy.

"We know that about 196 million Indians are undernourished, but 135 million are overweight or obese which means they are at risk of non-communicable diseases like high blood pressure, heart disease and diabetes.

"As well as these problems with the type of food people are eating, there’s also a problem with quality. The number of cases of food borne illnesses is predicted to rise from about 100 million in 2013, to anything up to 177 million by 2030.

"These infections affect people’s immune system function and their ability to absorb nutrients, which makes them vulnerable to more disease.

"Through food testing we are promoting awareness of what good and bad food is, and there is now a mobile food testing lab so people can get things checked at the doorstep.

"We have a lot of ambitions - fortified foods to improve overall nutrition levels and reduce incidence of conditions such as stunting and wasting; reducing food insecurity and cases of non-communicable diseases; generating awareness of people’s right to safe foods, and addressing climate problems by educating people about what’s happening and what needs to be done.

"We are trying to improve the nutritional value of all the food eaten by our citizens. We are offering free meals for children in all our schools up to the age of 14, and we have developed kitchen gardens in schools and that has been extended across the whole city.

"Promoting plant-based foods is a way of reducing the effects of climate change. We are organising workshops and camps and reaching school children to tell them why these foods are nutritious. Children are learning about climate change in schools and we are educating them to make these changes.

"We are promoting renewed interest in millets which is a traditional food that’s also a super food. Millets are small seed grasses that are gluten-free and rich in nutrients, fibre, vitamins and proteins.

"They are used in bread, cookies and porridge. We are engaging the catering departments of schools to produce more recipes with millets. If you create new dishes with different names that will create new interest in the public.

"We know current food production and consumption practices are threatening the environment and the future of our planet. Food production is responsible for up to 30% of global greenhouse-gas emissions which is adding to global warming and climate change.

"At the same time as problems with food availability and waste from food production, waste from food that is thrown away accounts for another 6.7% of these greenhouse gas emissions. We have now set up collections of food from restaurants and caterers to pass on to needy people.

"We don’t have urban farming but there are farmers in the areas around Chandigarh so we are organising more markets for local farmers to bring their food into the city.

"All of these initiatives are helping people to focus on preventive healthcare by accessing safe, healthy food in an environmentally sustainable way."

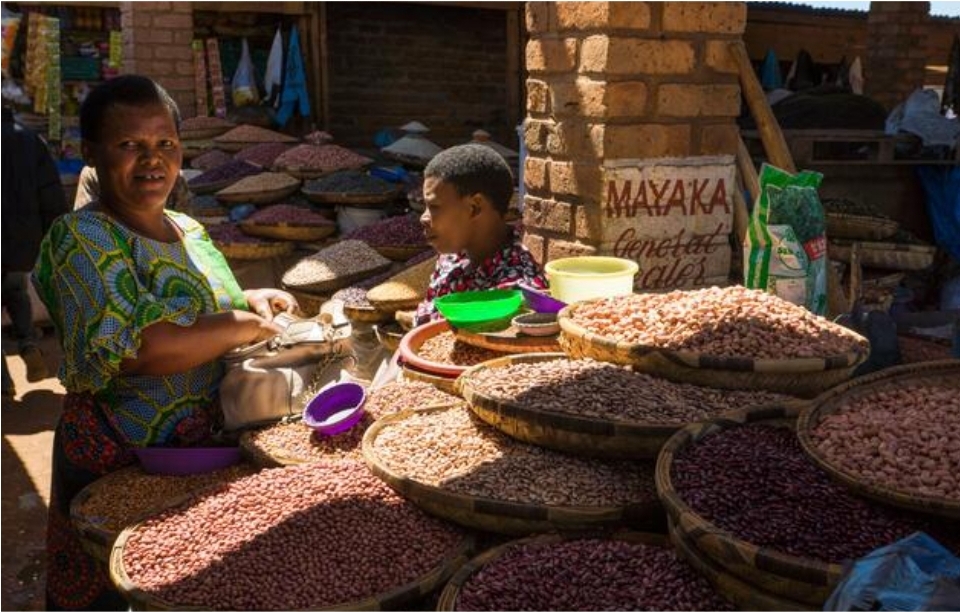

Catherine Mzumara, is Executive Director of Women in Sustainable Agriculture (WISA) in Mzuzu, a metropolitan hub in Northern Malawi with a population of around 220,000. She is an academic researcher and a farmer.

"WISA is a network of women in agribusinesses aimed at sharing ideas, learning from each other, and to empower each other especially rural women farmers who are struggling to put food on their tables. We are trying to help them to have sustainable livelihoods.

"I am also the strategic lead on food policy for Mzuzu City working hand in hand with the City Mayor, Gift Desire Nyirenda to make sure the city has a sustainable food system and improved nutritious diets.

"The city must have a self-reliant food system, we don’t have to bring in so much food from elsewhere which is becoming increasingly expensive.

"As a Food City, we are still behind compared to other food cities like Johannesburg, Durban and Nairobi that are already implementing their food policy, but we are trying our best.

"Mzuzu City has land that has been reserved for fishponds to develop and improve fish farming.

"However, we don’t have enough money to get it going yet. We’re also doing backyard gardening – teaching people to grow better more varied food on land they already own.

"We have just formed another small group of 500 women within the city to complement WISA and our Mzuzu food city project on urban farming. We’re calling it Friends of Mzuzu with the same framework of sharing ideas for more productive and efficient agriculture.

"This is our first year of planting vegetables which include kale and cabbages, carrots, and eggplants [aubergines]. Most women in high density areas of Mzuzu City do their washing up of dishes outside their houses and we are capitalising on this wastewater for the vegetables grown in sacks or their backyards.

"The city used to have a nursery for flowers. We are changing the tradition, thus planting fruit trees and vegetables instead of flowers.

"People who sell fruit seedlings or young plants mostly sell them at a high price but now the city will be selling them much more cheaply to anyone that wants them, and we are using grafting where you grow a new plant onto rootstock, to develop improved varieties of fruit that are suitable for the conditions.

"This new generation has just been planted – oranges, mangoes, avocado pears and peaches. We are looking at the women’s side, but we want everyone involved.

"A lot of people have moved into the city looking for work and have lost the tradition of growing things, but there is also a question of finding enough space to grow all the food we need.

"It’s true though, that most people will never have enough room to grow all their own food. Scarcity of land in the city and poverty hinders urban farming as 51% of the population here in Malawi live below the poverty line.

"We’re also planning to offer school gardening to promote school feeding by getting parents and school management committees to provide land that will be used for growing the ingredients for school meals. The schools and the community are very keen to take up the project.

"Food wastage is a huge problem in Mzuzu City. The first problem is post harvest food wastage. As a rain fed agricultural system, everything we grow matures at the same time, and we don’t have the infrastructure for storage.

"Our fruits, vegetables and all fresh foods have a very short shelf life. If they aren’t sold the same day, they simply go off.

"We are hoping to introduce indoor markets with solar powered cooling systems which will solve this problem.

"The second problem is food wastage after consumption. After cooking and eating, leftovers are thrown away because people don’t have cooling systems like fridges.

"Tradition and culture contribute to food wastage too. We don’t have a tradition of measuring food, when cooking, we measure the food with our eyes, and we have a huge amount that’s left over and thrown away.

"Culturally for us to know that everyone is full in the family, there must be some food left on the plate. The minority who own fridges also continue to hold on to the idea that they cannot eat something left over from lunch for dinner.

"Fridge owner or not, leftovers are destined for the bin. To tackle this challenge, WISA is organising a cook what you can eat campaign.

"Through this campaign, WISA want to educate women about measuring before cooking according to the number of people to consume it.

"The campaign will also encourage the new practice of freezing leftovers so they can be used for a future meal.

"The other problem is food waste disposal. At the moment, people are struggling to separate plastics and food waste.

"We are trying to instil a habit of separating waste in order to have food waste used separately for compost to grow more food.

"We are putting a lot of effort into looking at the food systems of other countries and cities, learning from them and putting ideas into practice. That’s the way forward for all of us."

Shushanta Kumer Das is the mayor of Nowapara, another rapidly growing inland city in southern Bangladesh, taking in climate refugees who can no longer survive storms and flooding which have swept away their homes and farmland. Leaders of the community of around 300,000 people are also hoping to draw ideas for solutions to the problems of food security through membership of The Food Foundation’s Food Cities network.

"Nowapara is a business and industrial centre, and as a commercial and communications hub, we are experiencing a constant influx of people looking for jobs.

"A lot of them move here without their families so they are long term users of our restaurants and hotels. There is lack of knowledge about to food.

"The lower and lower-middle income people are not always aware of nutrition issues and what good and bad food is, and it is as expensive here as it is in the capital Dhaka.

"We are working to secure proper management of the distribution of food which they receive from the central government.

"Land prices are increasing due to industrial developments around the city and as a result the availability of farmland is decreasing day by day.

"We have an interest in city-based farming for ensuring nutrition, but we can’t provide or ensure enough good seeds and fertilisers to everyone who is interested because we just can’t get enough stock.

"This increases the dependency of Nowapara on imported food, especially fresh food items for citizens.

"We have now set up a regular monitoring system to ensure food safety and we are monitoring market activity as well as food quality and quantity in the bazaars to ensure prices are fair.

"We need more communication, collaboration and particularly funding, from the sub-district level administration.

"We would also like more help from the non-government aid agencies but they are also very stretched, and like everyone else we have suffered a lot during the Covid pandemic so we are just getting back on our feet with things now."

Beryl Okundi, is director of stakeholder management and public communications at Nairobi city county government in Kenya, helping to drive a new agenda to promote food security. She is the main contact point for The Food Foundation’s Food Cities project in Kenya.

"At the moment about 20% of Nairobi’s population of around four million people suffers from food poverty.

"Our Mayor Anne Kananu is in charge of affordable nutritious and safe food for all Nairobi residents and has recently agreed a new food security system strategy, a blueprint that identifies the challenges and initiatives needed for food provision.

"This is a very detailed document describing the plans to increase local food production, stabilise food supply and producer incomes, reduce food loss and wastage and improve the health and welfare of consumers.

"At least a quarter of the city population have backyard gardens or shambas as we call them, which can be used for urban agriculture to grow more fruit and vegetables.

"A lot of urban farming can be done in the poorer areas because they actually have more space. The more expensive parts of the city don’t have shambas at all.

"We have set up all sorts of public participation events to promote urban agriculture. We have agricultural officers going into the community and we register people interested in taking up urban farming.

"There are then training sessions where we teach them the best processes and techniques for growing food, transporting and marketing it, and the requirements of trading and consumer laws.

"People did this in the past but there wasn’t a great deal of interest or any kind of platform promoting it and not that many people are tuned in with food and farming issues.

"Now we are pointing people towards these ideas and the urban farming sector is becoming really vibrant.

"Sukuma wiki which is like kale, spinach, carrots, tomatoes, onions, and all sorts of other small scale foods are being grown.

"People have been driving out of town and burning fuel to buy something when they have healthy soil to grow in their backyards, so this is cutting costs of going to get food and utilising what people already have.

"We have a big problem with global warming and climate change. If the long rainy season and the short rainy system are reversed that makes things hard.

"Water supply in Nairobi can be difficult. The city relies on the reservoir behind the Masinga Dam on the Tana river which is the longest river in Kenya. If there’s reduced water in the river that affects water supply in Nairobi.

"We are supporting a programme to clean up local rivers and we’re encouraging our would-be urban farmers to harvest rainwater off roofs, recycle domestic water, use bore holes, water butts and so on.

"Existing agricultural land is being protected from building development with a system of zoning, and food production and agribusinesses are being supported with a programme of incentives alongside a parallel programme to sort out and improve poor quality agricultural output.

"We are showing people that it’s quite easy to reconnect with the earth and you don’t have to have a farm to earn money from farming.

"There is a forthcoming international trade fair in Nairobi where the agricultural sector has a huge showroom where they will engage would-be urban farmers. These are opportunities for people to network.

"We are very keen to connect with like-minded people and organisations to see what they’re doing in terms of dealing with food security issues which is why the Food Cities project is so useful."

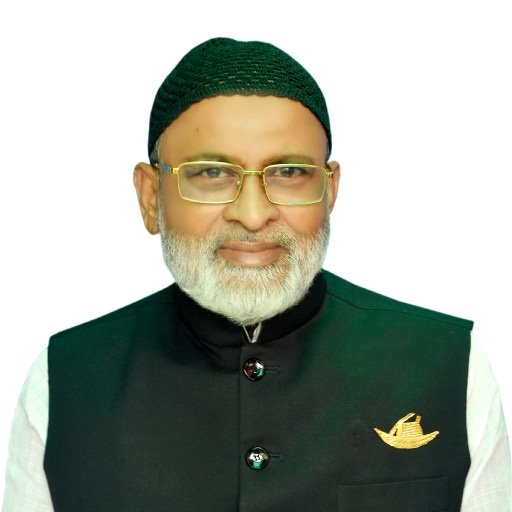

Sheikh Abdur Rahman, Mayor of Mongla Port, a riverside coastal city of 150,000 people which recently joined The Food Foundation’s Food Cities project. His community is facing major challenges in finding ways to provide adequate food for the population in the face of rapid climate change

"As a growing city, Mongla faces huge pressures and demand for food supply.

"We are Bangladesh’s second largest seaport and climate refugees from other parts of the country are shifting to our special economic zone in the hope of finding work, but with this growing demand, we are facing new issues related to food system and security.

"As a disaster prone and vulnerable area, it’s difficult to grow enough crops to meet the demand.

"The chances of creating a homestead garden or setting up city-based small scale fruit and vegetable production are limited because the ground is affected by salinity intrusion - saltwater flooding.

"There are several systems for ensuring widows, older people and children are helped. Besides the ultra-poor and poor, people in need also get extra food support during the festivals.

"We are working to ensure a better supply of clean water and we are distributing selected seeds for rice crops that have been bred from strains that are better able to resist a salt-laden environment, as well as fertilisers and water purifiers donated by different aid providers and charities.

"We are seeing the effects of climate change, rising sea levels, river erosion and frequent severe storms, as well as the salt water encroaching on farm land.

"Flooding is a constant problem here and we are seeing millions of people losing their homes and land, but we want Mongla to be recognised as place that can be climate resilient.

"Cyclones with their strong winds and associated flooding are more and more common. But the floods that happen in southern Bangladesh are more transitory than those in the north.

"Dealing with the agricultural problems caused by salinity intrusion is a problem but we are developing crops that are resistant to this.

"We are very pleased to be part of the Food Cities network because it’s a great way to share ideas and get to know about the other developing and developed municipalities, how they work and cope with different problems.

"It’s good to learn from other people and get solutions that we can implement in Mongla according to necessity."

James Kalundu from Namibia, took a master’s degree in international rural development at Birmingham University 20 years ago. He is now a social and youth development programme manager in Namibia’s capital Windhoek, which has a population of around 270,000 and is in the vanguard of the urban farming movement.

"Urban farming of nutritious foods is among the key innovations we’re developing in Windhoek and we’re very keen to show our progress so far and share our ideas for local solutions to global food problems with other cities.

"Urban agriculture is a new concept for Windhoek and a fairly new kid on the block for all of us working in this area.

"Historically there was no agriculture here, we are pretty much a desert community, but with recurring drought and climate change we realised that even places that were exporting food to us were struggling.

"Rainfall in areas which expect 900mm to 1,000mm per annum have only been getting 600mm for the past four or five years. We need to find ways to become a self-sustaining city.

"It all started for us with the signing of the Milan Pact which is based in Italy and now includes around 200 global cities working to share ideas for the development of sustainable, inclusive food systems which provide healthy affordable food for everyone within a human rights framework minimising waste and preserving biodiversity, at the same time as tackling the impact of climate change.

"After we signed the Pact there were exchange programmes for our leaders to see how other people are doing it, which is how we got involved with The Food Foundation's work and with Birmingham City Council, which is also working to spread these ideas.

"We are establishing at least six community shared ‘gardens’ or plots of land in Windhoek, as well as growing areas in every domestic back yard and gardens around schools to provide food for pupils.

"The first shared garden that’s currently being developed is 2,000 hectares - 2,000 sports fields. It’s called Okukuna which means cultivating with your hands in one of our 11 local languages.

"The farm is in an area with 70,000 people within walking distance and most of them are in need of food.

"At the moment we’re developing the farm incrementally, we so far have 1,000 hectares being farmed and 100 people employed.

"The second farm in another part of the city will also be 2,000 hectares but 1,000 of it will be for training including animal husbandry - goats, cows and poultry, as well as fruit trees.

"We’re also planting other fast growing trees that can grow two to three meters in two years, for shade and cleaner air. The target for the second farm is to involve another 200 to 300 people.

"We have worked out how to supply irrigation and there are two systems of clean and semi purified water pipes and a bore hole that will be solar driven.

"Every allotment will be 100 square metres and fed by a drip irrigation system. We have categories of people we’re helping – disabled people and destitute homeless street kids who we’re bringing them to the farm and training.

"Each 100 square metre plot should provide food for six people. The surplus can be swapped with neighbours and the rest can go to market.

"There should be enough for everyone in the community and it should be possible to grow much more on a smaller space.

"This is farmland that historically belonged to the city of Windhoek. When the leases expire the land passes to the city.

"We have been focusing on the staple food people enjoy. People eat a lot of beef and a lot of maize mielie pap which is a type of porridge. We mix it with onions, spinach, carrots, beetroot lettuce and herbs.

"Some of the fruit trees are starting to bear fruit. We have skilled horticulturalists advising on what fertilisers to put down and what must be done at what time of year. We have planted guava, lemons, oranges, avocado, peach, mango and bananas.

"I believe if we do this correctly we can feed a huge number of people. The potential is huge.

"Okukundu is so popular we have contracts with two supermarkets and restaurants and we are selling to individuals. This scheme can provide food security at a household level and has great commercial potential."

Pictures from the event

City leaders signing the Food Justice Pledge

Dr Alan Dangour talking about the climate crisis

Speakers at the major food supply chain challenges session

Some of the delegates leading change in their cities

A networking event on the sidelines of the conference

Full videos of the conference

The opening session of Commonwealth Food Futures 2022

Addressing the dual burden of obesity and undernutrition

Which cities are leading food system transformation?

How cities are responding to the climate crisis

African women transforming food systems

India's role in creating more sustainable food policies

Major food supply chain challenges facing cities

Cities sign the Birmingham Food Justice Pledge