Please note if viewing the exhibition page via a mobile phone view it in landscape mode for the best experience.

Citizens’ voices are a powerful part of The Food Foundation’s work. Our Food Ambassador programme consists of a community of citizens from across the UK who are passionate about changing the food system.

Crucially, the programme aims to amplify the voices of people with lived experience of food insecurity in decision-making processes, research and the media so we worked with eight Food Ambassadors on a Photo-Storytelling Project to bring light to the realities behind the statistics in the 2025 Broken Plate report.

The project was inspired by the work of PhotoVoice, an organisation that supports the design and delivery of participatory photography, digital storytelling and self-advocacy projects for underrepresented or issue-affected groups. Using the medium of photography, the Food Ambassadors have described their food environments in order to convey their personal perspectives of the broken food system.

Across these pieces, the theme of food insecurity is consistent, intertwining with fuel poverty, housing, parenthood, culture, disability, nutrition and health. Each set of photographs is captioned and accompanied by an audio recording. To understand the ambassadors’ work, take time to read the captions and listen to their voices. The photographs alone only tell part of the story.

Use the audio player below to listen to Caroline speak about their work.

Packaging made so colourful and bright

Made to look like a special delight

This grabs your attention and the children's too

But the sugar inside is hidden, that's true

This really isn't affordable food

And the sugars inside aren't good for the brood

Where are the real healthy snacks?

The food that's good isn't in colourful packs

Dan White, Fareham

Use the audio player below to listen to Dan speak about their work.

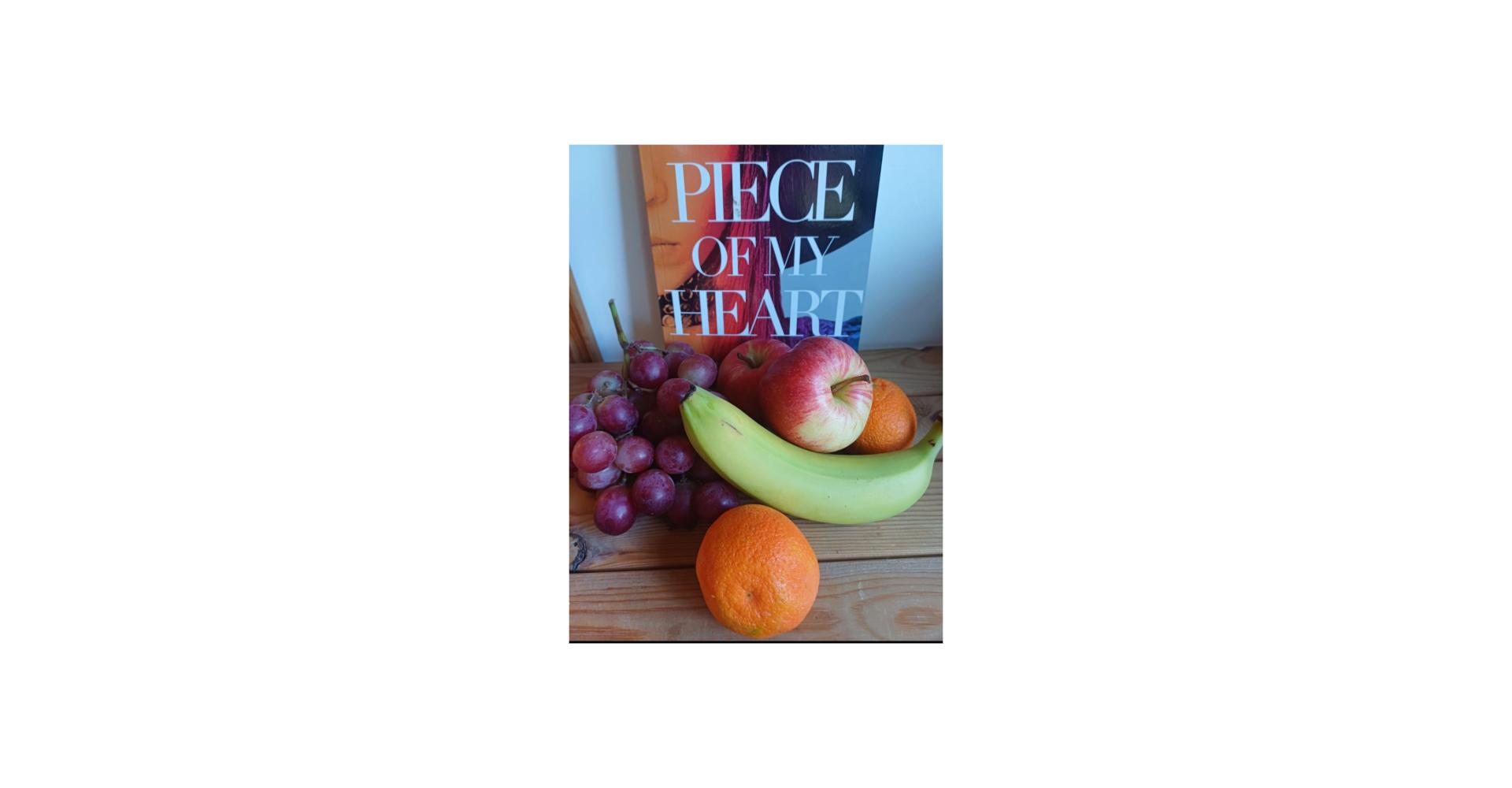

Poverty is nothing new for the Disabled community. Poverty has always been a constant for many who have a disability. Stereotypes, low benefits, societal neglect, political disdain, discrimination – poverty is nothing new.

And food poverty is part of this. Right now, many Disabled people are skipping meals because households with a Disabled person are more likely to experience food insecurity than those without.

Food insecurity for Disabled people means being unable to afford food and as a result having smaller meals than usual or skipping meals; being hungry but not eating because of food costs; or not eating for a whole day. For someone with complex health needs, this can be catastrophic. Pushing people back to low paid, precarious work is not a route out of poverty.

Confidence and pride are finally broken when the only option is the foodbank.

For Disabled people, foodbanks are often not able to meet their needs at all despite their best efforts. There can be physical barriers to access, where they cannot travel to a foodbank, or even barriers to physically access the foodbank. Foodbanks are often unable to cater to specific dietary requirements which are more common among Disabled people, often resulting in a worsening of people’s health.

So, the circle of poverty around food, of access to food, of financial ability to buy food, goes around and around.

Foodbanks are not the solution. Targeted support and co-operation with the community is. The alternative is a humanitarian crisis on our doorstep.

‘This image shows the brutal reality of disability food poverty. It shows that poverty has always been a constant for the Disabled community. The broken chair represents broken spirit, broken promises from the political system to improve their lives for the better. The shelves are stacked, but for someone with a physical disability, always too high, too far out of reach, much like the better life always promised… but never delivered. Never, ever, ever delivered.’

Food issues intersect with poverty issues, which relate to housing, space and the complete non-recognition of unpaid domestic labour. This government and former governments have put an emphasis on ‘work’ above all else, whilst completely failing to recognise the time and energy that goes into preparing healthy food. Forcing single parents back to work has a detrimental effect on their ability to provide for their children.

Unpaid domestic labour is the backbone of society and provides for us all. If we want to move towards a healthy and sustainable diet and future for our children, we need to recognise this and ensure that mothers are adequately provided for when it comes to money and housing. At the moment, the housing crisis and the complete stigmatisation of the benefits system means providing adequately for our children is a pipe dream.

Use the audio player below to listen to Glory speak about their work.

The lack of culturally appropriate food in schools influences dietary behaviour. I wanted to show what a healthy food environment looks like through my photos: when culture meets nutrition.

When these healthy choices are unavailable, unaffordable, inaccessible and unappetising, people will go for food lower in nutritional value. Children skip lunch at school because the offering doesn’t align with their cultural needs. This will hinder their learning and development.

Policymakers can create a fairer UK by fostering a healthier food environment. A government that supports culturally appropriate Free School Meals fosters inclusivity, respect for diversity, and better nutrition for low-income families. I also want to see the government support communities with grants that fund food education and allow people to grow and cook their own food. This is not just about diet – it’s about cultural diversity through food, which can also educate people, especially children, about different cultures and skills.

We want thriving and cohesive communities, and this can only happen when we include everyone.

Use the audio player below to listen to Magda speak about ther work.

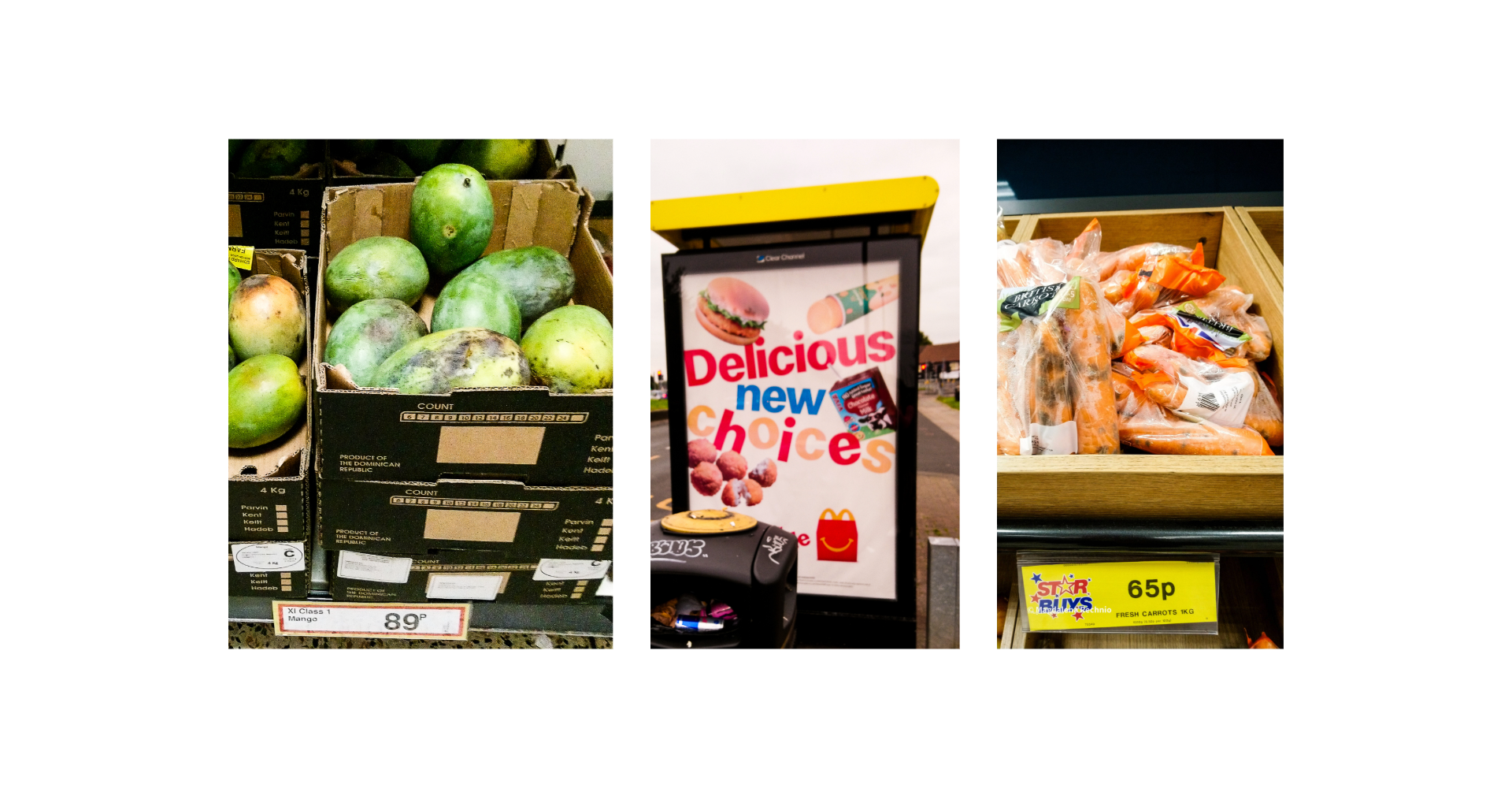

In 21st century Liverpool: affordable fresh fruit and vegetables in shops should not be an exception.

In 21st century Liverpool: spoiled and mouldy fruit and vegetables in shops shouldn't be a norm (they are near me).

In 21st century Liverpool: the closest greengrocers shouldn’t be 2.2 miles away from home.

In 21st century Liverpool: everyone should be able to afford to buy vegetables and fruit from the greengrocers.

In 21st century Liverpool: we should not be teased with junk food advertising ‘delicious new choices’ and free junk food (buy one get one free) which are high in fat, sugar and salt.

In 21st century Liverpool: junk food should not be cheaper and easier to obtain than nutritious food.

Make healthier options more appealing, and ban junk food advertising in physical and online environments.

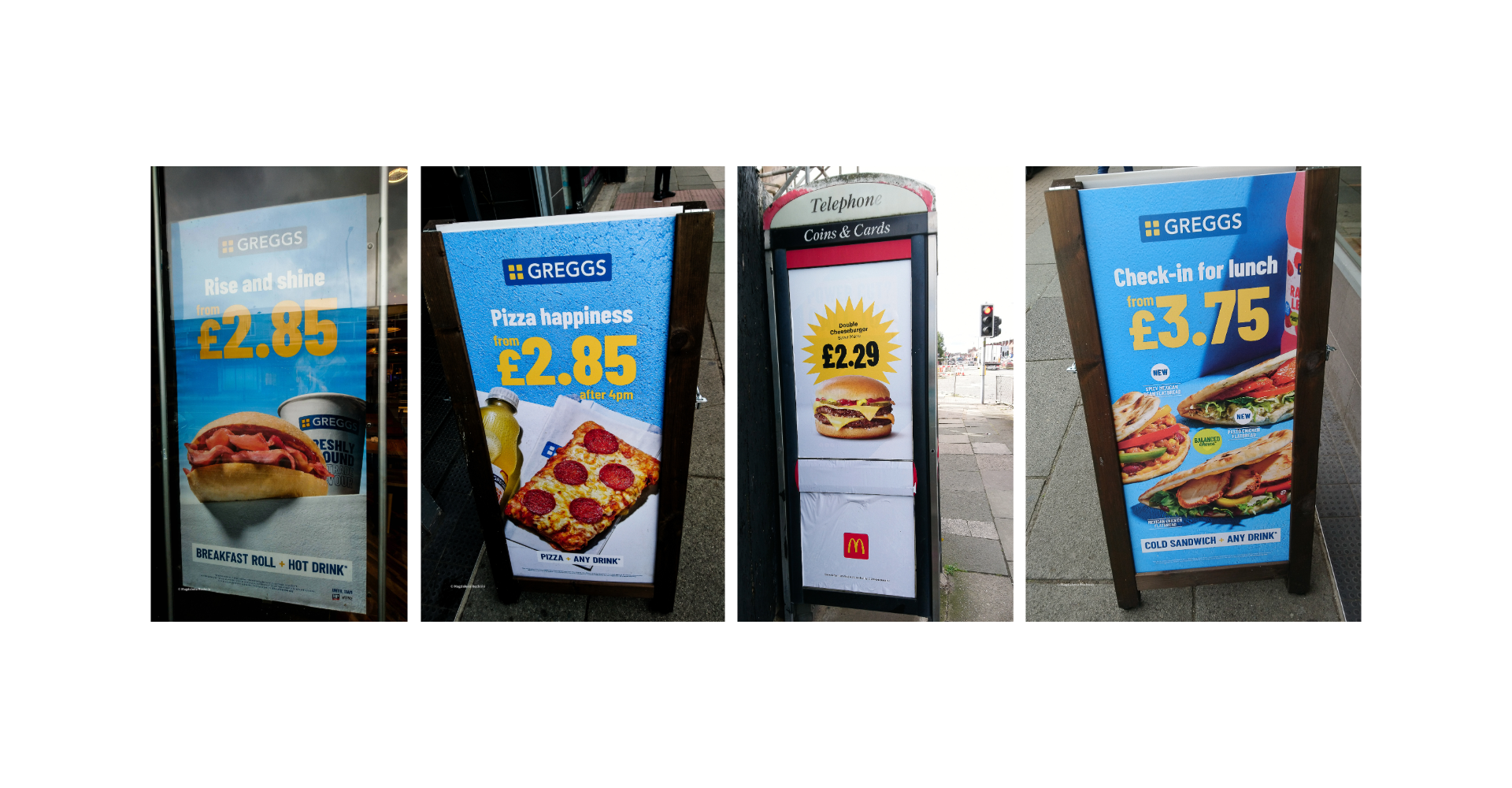

Hungry?

The healthier option costs nearly £1 more than ‘pizza happiness’ or a ‘rise and shine’ bacon bap. It costs £1.46 more than the double cheeseburger! In a year, choosing the healthier ‘budget’ option 5 days a week could add up to from £216 to over £350.

In 21st century Britain: we should not be bombarded with junk food advertising on the streets, in stores, on TV, online and on our phones – especially not our children.

Get rid of the gap in healthy life expectancy between the richest and poorest regions by investing in healthier food for all.

Invest in Britain: help us afford and access nutritious food, alleviate pressure on the NHS and build a better food future for all.

Wena Isename, Edinburgh

Use the audio player below to listen to Wena speak about ther work.

Decision:

On one side you have food insecurity depicted as a bare and dry tree, while on the other, a luscious thriving tree depicts a society where consumers, our health and environment are prioritized. The building behind the trees signifies the closed walls of the government, making decisions for us. Their eyes are open and yet we are not seen. The cars on the road signify us: knocking on the doors of the government, saying ‘let us in, we deserve a seat at the table’.

Choices:

When it comes to the basic necessities of life – including food – the government, businesses and postcodes decide for us. The three apples signify this reality: the whole apple signifies big food corporations who decides on procurement, supply and demand; the apple with a small bite signifies the government who makes the choices of affordability and availability; and the threadbare apple signifies the consumers who suffer the fate of the choices.

Measurement:

‘Eat, shop according to your need, avoid waste’ – an ideal and appealing future, and unaffordable and unavailable present.

Kathleen Kerridge - Portsmouth

Use the audio player below to listen to Kathleen speak about their work.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) costs the NHS £7.4 billion and the economy an estimated £15.8 billion a year in England. The NHS puts eating a healthy diet as the number one way to prevent CVD and heart attacks.

When the costs are so high, why is it so hard to afford a healthy diet? Increase benefits, increase wages, improve health. Make food affordable and a healthy population follows.

Use the audio player below to listen to Dominic speak about their work.

We live in the most deprived blocks of this council estate, where our access to nutrition is overlooked.

The shop on the estate only sells the lowest quality of ultra-processed food, making this a food desert in the Garden of England.

This is what fuel poverty looks like – regularly we don't have enough gas or electric to cook with raw ingredients.

This is where the bus never shows up. It's hard to make it out of here.