14 December 2023

Was COP28 a win for food systems?

Our Responsible Investment Engagement Lead Sarah Buszard was in Dubai for COP28. Here she examines whether its outcomes will lead to the lasting change our food systems urgently need

There’s been quite a bit of attention by the food community on this year’s Conference of the Parties, or COP as it’s more commonly known, which has just concluded with an agreement by almost 200 countries to transition away from fossils fuels and ramp up renewable energy. But there’s been a lot more on the agenda than just fossil fuels.

First, a little bit of background. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change - or UNFCCC - entered into force in 1994 and is the parent convention for the Paris Agreement, which was adopted at COP21 in 2015.

The countries who are state parties to the UNFCCC come together annually at COP to discuss a wide range of topics related to the implementation of the convention’s provisions.

This year at COP28, food was featured much more prominently on the agenda than ever before.

That’s important because we know that food systems are currently responsible for 90% of global deforestation, 70% of biodiversity loss, a third of global greenhouse gas emissions and use 70% of our global freshwater supplies.

And that is having negative impacts on yields, food security, resilience, soil health and the nutrients in the foods we produce. Severe weather events are already affecting our ability to produce and transport food, and that is threatening our ability to provide healthy diets for all.

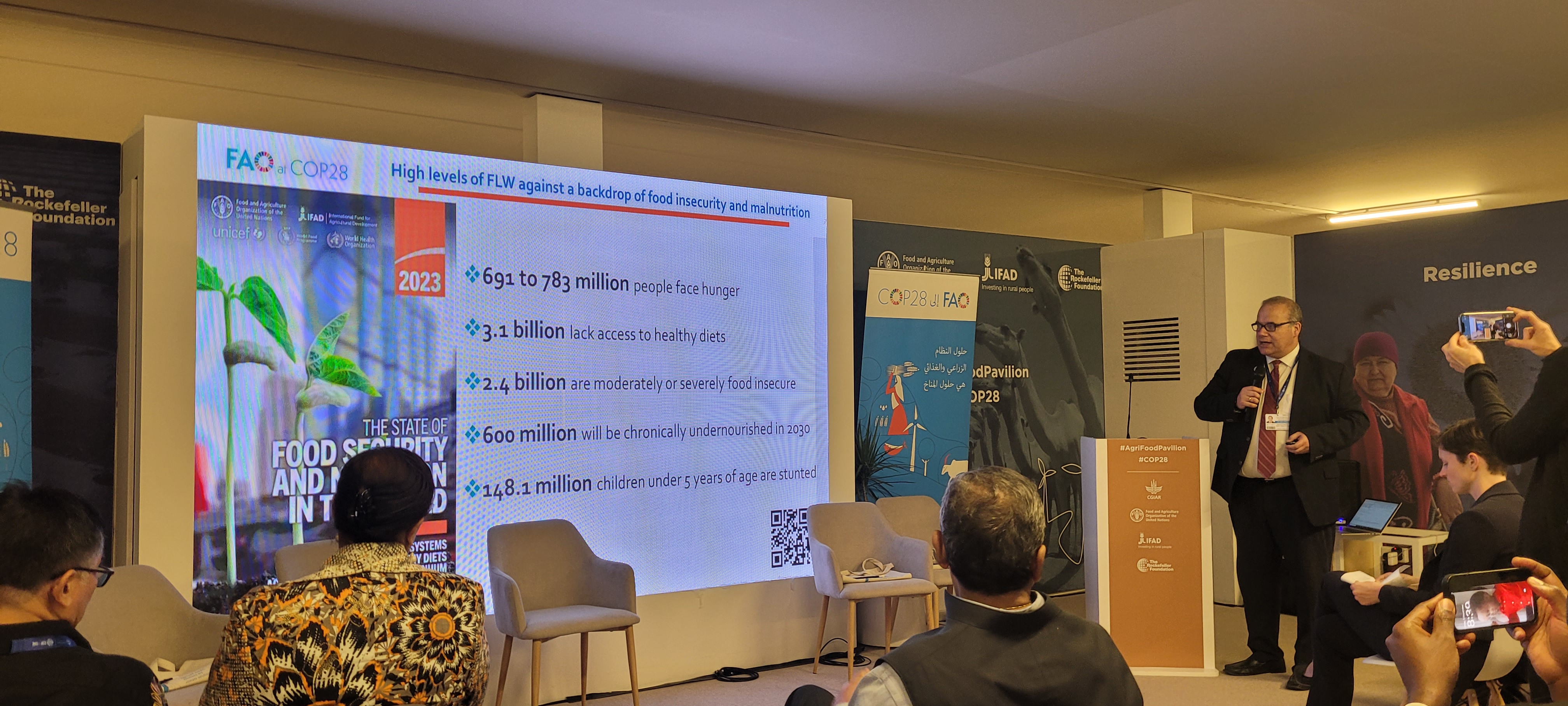

This COP also saw the first ever "Health Day" on 3rd December. The World Health Organisation has predicted that between 2030 and 2050 climate change will cause an extra 250,000 deaths per year from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat stress. Our current food system is already failing billions around the world.

The Food Foundation and Investor Coalition on Food Policy event

Given the focus on food and health in the context of a global climate conference, the Food Foundation and the Investor Coalition on Food Policy decided to hold a side event on Health Day at COP.

Investors have not traditionally been part of the multi-stakeholder dialogue around food systems transformation, and yet they have significant potential to help transform the systems.

Investors are increasingly aware of the material financial risks of failing to make healthier and more sustainable diets affordable and accessible for everyone.

Given these risks, food systems really do need to be more integrated into Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) considerations because it creates the opportunity to join up the dots between climate, food security, nutrition, and health.

Our session at COP28

The focus of our side event was on how investors can help, looking at the role of data, transparency, standards and regulation as part of food systems transformation.

We were joined on the panel by Nicola Day, the Deputy Head of Greenbank Investments; Lauren Compere, the Managing Director and Head of Stewardship and Engagement at Boston Common Asset Management; and John Willis, the Director of Research at Planet Tracker.

Our panel discussed why institutional investors are interested in food systems transformation, what the main financial risks are that the global food system is facing if we continue with business as usual, and how investors are managing these.

We also discussed the main trends and barriers in terms of a transition to a healthy and sustainable global food system, those the investment community faces in aligning their investments with healthy and sustainable food systems transformation, and the extent to which the lack of transparency in the food and drink sector is an obstacle to investment in healthier and more sustainable foods.

In fact, the difficulty of getting reliable, accurate, and comparable data was a common theme across many of the sessions at COP. The regulatory landscape is changing and investors and businesses can’t ignore it.

The regulatory direction on global corporate reporting offers a huge opportunity for systems change and a shift in food culture.

More action from food businesses is absolutely needed, but big shifts in the food environment can only be achieved by shifting the incentives and standards in the system within which businesses operate.

And it’s governments who are responsible for changing these parameters and incentives. And while it’s not the whole picture, having clear, accurate, reliable, comparable data that is legislated for is a critical part of the solution in the transition to healthy, sustainable food system that works for people and the planet.

What else happened at COP28?

Declarations

Early on at COP we saw the launch of two declarations:

- The first was the COP28 UAE Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems, and Climate Action. This is a head of state level declaration and has been signed by over 150 countries, including the UK. What’s good to see in this declaration is food systems – and food systems transformation – being recognised as needing to be included to achieve fully the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement. There are also references to food security and access to safe, sufficient, affordable, and nutritious food for all, which is really positive. One aspect that was missing however, was the need to shift to more plant-based foods.

- The second declaration was the COP28 UAE Declaration on Climate and Health. This is a ministry-level declaration and has been endorsed by over 140 countries so far, including the UK. It’s a global commitment to address climate-related health impacts and align climate and health in policy processes. It’s good to see references to food, nutrition and a shift to healthy sustainable diets mentioned in this – as well as combating inequalities, reducing poverty and hunger, improving health and livelihoods, and strengthening social protection systems. It would have been nice to see more on actual food systems transformation though.

While these declarations don’t have any legal standing, they do put food and health and the link with climate firmly in the global space going forwards, so that should help to mainstream climate action and join up the dots across policy agendas and actions related to food and health.

The Food Declaration requires the signatories to build the commitments into their National Adaptation Plans, Nationally Determined Contributions, long-term strategies, National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans, and other related strategies before COP30 (2025). Progress will be reviewed collectively at the next COP in 2024.

The Health Declaration requires the signatories to build the commitments into Paris Agreement and UNFCCC processes, National Adaptation Plans, Nationally Determined Contributions, and low Greenhouse Gas emissions strategies.

And progress will be reviewed at future COPs. So we welcome the UK government endorsing both of these Declarations, and there is now an additional imperative for the government to implement reporting requirements that will facilitate its own progress on, and monitoring of, its international commitments.

Global Stocktake, Global Goal on Adaptation, and the FAO Roadmap

One of the major outcomes of this COP was the countries’ response to the first Global Stocktake against the Paris Agreement goals.

Most of the wrangling was over the issue of fossil fuels, but there was also a fair amount of back and forth on food-related matters and whether they would even be reflected in the final decision.

This was also the case for the Global Goal on Adaptation, another key outcome from this year’s COP. The good news is that some food and nutrition-related references have found their way into the final texts, even if not as prominently as we would have liked to see.

The UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation, the FAO, also released their Global Roadmap for Achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2 (zero hunger) without breaching the 1.5C threshold.

This is a pathway for aligning the global food system with global climate goals. It recognises the importance of dietary shifts and changing the food environment.

It also highlighted the need to cut food waste by half and reduce methane emissions from livestock by 25% by 2030, and also plant more diverse ranges of crops than we currently do.

The roadmap says that different countries also need to take different measures; for example in northern, higher income countries, governments will need to nudge their citizens to reduce their meat and dairy intake.

There’s a section on intensifying livestock production in relevant locations, which isn’t the direction we would want to see food production going in, given its health and environmental consequences.

Other global organisations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change more explicitly recommend that meat and dairy consumption ought to be reduced in order for us to keep emissions within 1.5C.

While the roadmap might be looking at the issue of livestock through the low-income livelihoods lens, this also fails to also take into account animal welfare, which is often sacrificed with more intensive livestock production systems.

Final thoughts

The health lens has added urgency to tackling the climate crisis, but we still need to see more focus on the nutrition aspect on the food, climate and health nexus.

But if we take all these relatively modest steps that took place at COP28 together, they can be seen as an affirmation of the importance of food, health and nutrition in the global context of tackling climate change.

While perhaps still an emerging agenda on the world stage, these steps have laid the foundations for ramping up work on food systems transformation going forward, so let’s take that as a win and get back to work!