31 October 2024

Triple wins for children's poverty food insecurity and health

Triple wins: Ending the need for food banks, reducing child poverty and creating the healthiest generation of children ever, by Food Foundation Policy and Advocacy Manager Shona Goudie

The newly elected Labour Government face an urgent crisis of child poverty and food insecurity, which has far-reaching consequences on the health of the nation.

The Labour Party manifesto published earlier this year made bold promises to address these challenges aiming to ‘end mass dependence on emergency food parcels’, create an ‘ambitious strategy to reduce child poverty’ and create ‘the healthiest generation of children ever’.

These commitments offer a critical opportunity to bring about transformative change and help the millions of people across the country who are struggling as well as strengthen the workforce, healthcare system and economy.

Picture: Impact on Urban Health

As Labour enters its first year of Government, how can they deliver on these ambitious promises to the UK public?

The scale of the challenge

Food insecurity

Before austerity, food banks were an emergency resource to help people get by for a few days in the face of unexpected shocks. But they have become normalised in our society with staggering numbers of people reliant on them on a long-term basis to prevent hunger.

Alarmingly, the UK now has almost twice as many food banks as McDonalds, with food bank use having increased by 94% in the past five years according to Trussell data.

However, food bank usage represents the tip of the iceberg that is food insecurity. Research from the Food Foundation’s Food Insecurity Tracker reveals that approximately one in seven households are food insecure in the UK, meaning millions of people cannot consistently access enough nutritious food. (For more, see our food insecurity tracker).

There are many reasons why people struggling to access sufficient food might not turn to food banks for support, such as stigma and shame. Despite volunteers best efforts, food banks’ dependency on volunteers, donations and food surplus means that they cannot reliably always meet the level of demand or provide adequate nutritional provision.

This is particularly problematic for people with medical dietary requirements and people requiring culturally appropriate food. People simply have to take what they’re given with no dignity or choice. It is clear that food banks are therefore not an adequate long-term solution.

Health inequalities

Food insecurity is a severe manifestation of poverty, both of which are inextricably linked with health. Food insecurity is not merely the ability to afford and access enough food as is captured by our survey data, but food which provides sufficient nutrition to facilitate good health and prevent disease.

Millions more people are compromising their health due to financial constraints pushing them towards cheaper options, which tend to be filling due to their high calories but are lacking in sufficient nutrients to properly fuel the body.

This is driving the stark health inequalities we see in the UK. For example, a child in the most deprived fifth of the population is twice as likely to be living with obesity as their peer in the least deprived fifth.

Similar patterns are seen in other diet-related conditions such as dental decay and type 2 diabetes, among many others. (For more, see our Children’s Right2Food dashboard).

The government’s goal to “create the healthiest generation of children ever” hinges on tackling these inequalities by improving access to nourishing food for the poorest children in society.

A roadmap for Labour to achieve these goals

This illustrates the scale of the challenge that Labour faces, but there is a clear way forward for them to reverse this grim picture. Strategic action to tackle food insecurity and ensure low-income families can afford and access a healthy diet can make a meaningful dent in delivering on multiple goals.

There are two key areas where transformational policy is needed: firstly, ensuring all families have sufficient income to afford a healthy diet and, secondly, strengthening nutritional safety net schemes that specifically support low-income children.

1. Increase incomes for the most deprived families to be able to afford to eat nourishing food

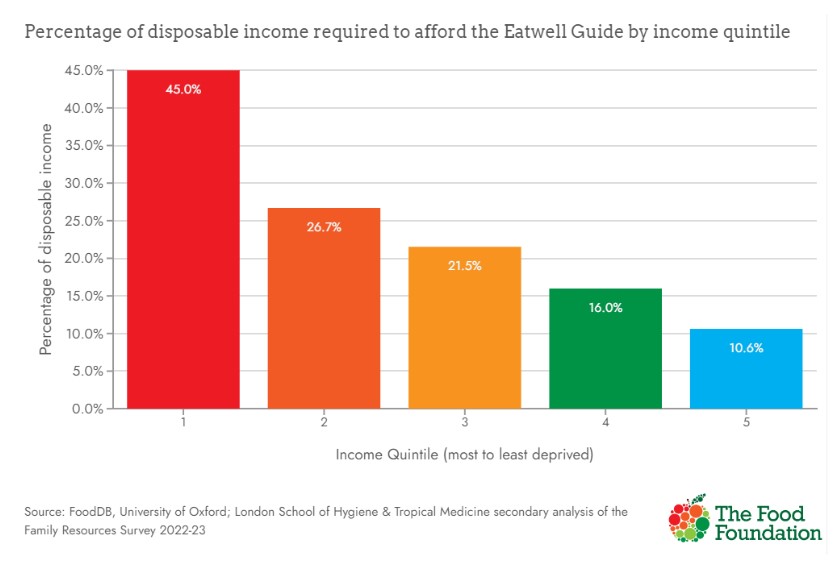

Newly updated annual Food Foundation analysis reveals that the poorest fifth of the population, would need to spend 45% of their disposable income on food to afford a diet in line with the Eatwell Guide, the government recommended healthy diet. This is far from feasible or realistic.

Given these findings, it is hardly surprising that there are such high levels of food insecurity in the UK, with millions of people simply unable to afford sufficient food, and millions more relying on food of limited nutritional value.

This has decreased since the peak of the cost of living crisis (50% in 2021-22) but remains higher than the previous year (42% in 2020-21).

In stark contrast, households in the most well off fifth of the population would have to spend just 11% of their income to afford a healthy diet. This disparity explains the sizeable contrast in dietary health between the most and least well-off groups.

A clear solution is to increase incomes for the poorest in society so that they are not trapped in food insecurity and priced out of a healthy diet. Currently, neither benefit levels nor the national living wage are calculated based on the cost of the basic essentials, leaving many low income families without sufficient money to afford the food they need.

Wes Streeting recently commented that “we don’t want to encourage a dependency culture where people think it’s OK not to bother eating healthily”.

If government are to expect people to eat in a way that does not damage their health and follow their own guidelines on meeting nutritional requirements, they need to ensure that families have sufficient income to do so.

The government has recognised the shortcomings of the social security system, committing in their manifesto to review Universal Credit to ‘make work pay and tackle poverty’.

Benefits must be adequate to support people who are unable to work - whether due to disabilities, being single parents or other reasons – to be able to afford to eat a diet that is not harmful to them and, therefore, doesn’t result in them needing NHS support to treat their diet-related conditions.

It is also critical that workers are fairly paid. Labour have changed the remit of the independent Low Pay Commission so it will take account of the cost of living for the first time.

Through both these processes, policy should be changed to ensure that the cost of healthy diets is taken into account when setting benefits levels and the living wage. For more see our briefing on benefits and wages here

2. Make government’s nutritional safety net schemes for children fit for purpose

In addition to addressing income barriers, additional measures are needed to specifically support our children, due to the significantly higher risk of experiencing food insecurity and the more detrimental impact that it can have on them.

Our most recent survey carried out in June found that almost one in five households with children were food insecure - 54% more than those without children. The physical and mental health impact of this on children across the country cannot be overstated.

The deterioration of children’s health in this country in recent years is shocking: the average height of five-year-olds is falling, obesity levels have increased by almost a third and the number of young people being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes has risen by more than a fifth.

Children from the most deprived backgrounds are at greater risk of all of these health consequences. See our Neglected Generation report for more.

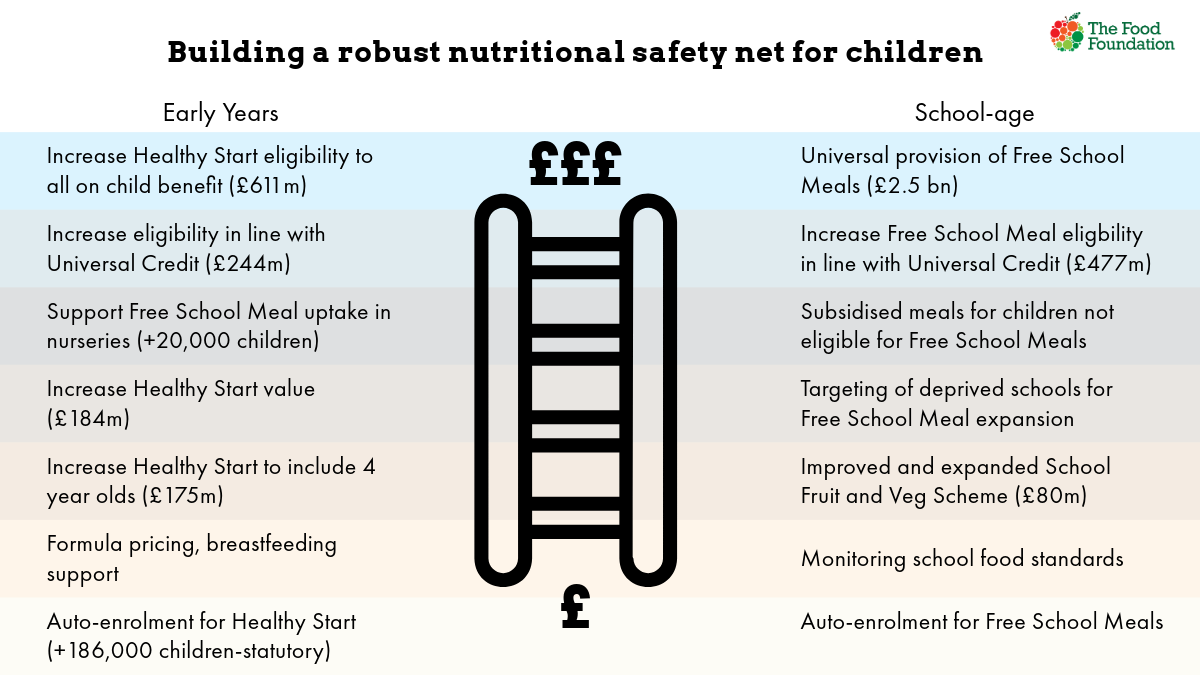

To address this, the Government must improve current nutritional safety net schemes. These schemes are an essential complement to policies to improve incomes that directly help low-income children to access healthy foods.

Free School Meals: Free School Meals in England are only available to children in families earning less than £7,400 per year after tax and benefits. This means that 900,000 children are in families who are living in poverty but earn more than this very low threshold and therefore so not qualify for the scheme. The scheme must be expanded to help these children. For more see our briefing on expanding Free School Meals here. On top of this, an estimated almost half a million children are eligible for the scheme but aren’t signed up. For more see our briefing on Free School Meal Auto-enrolment here.

Healthy Start: The Healthy Start scheme provides weekly payments of £4.25 to low-income families with children under four and pregnant women that can be used to purchase fruit, veg, milk and formula. However, as with Free School Meals, only families on incredibly low incomes qualify and there are many families who could be benefiting for the scheme but aren’t signed up. Eligibility for the scheme should be expanded to all those on Universal Credit with children under five, and eligible families should be automatically enrolled. For more see our briefing on Healthy Start here.

Holiday Activities and Food Programme: The Holiday Activities and Food Programme is a holiday scheme that is free for children eligible for Free School Meals during term time. This was introduced following the campaigning led by footballer Marcus Rashford during the pandemic. Three years of funding was committed to which expires after the 2024-25 academic year. The scheme should be made statutory with long term funding allocated.

Breakfast provision: Labour made the welcome commitment to introduce breakfast provision in all primary schools. Ensuring that the food served is nutritious for children will be critical to ensuring that this policy delivers on both tackling hunger and health inequalities. The introduction of monitoring of the government’s School Food Standards across the school day can help ensure that children dependent on breakfast and Free School Meals (lunch) are getting nutritious meals at school.

Next steps for the Government

While the UK faces significant fiscal challenges, investing in people – especially children – is critical for the country’s long-term health and prosperity. Ensuring all families can afford nutritious food can not only improve individual lives, but create a healthier, more resilient workforce and reduce healthcare costs.

The government has several key moments in the coming months to demonstrate their commitment to ending the need for food banks, reducing child poverty and creating the healthiest generation of children ever.

Namely, the Child Wellbeing Bill, the Child Poverty Strategy and the reviews of Universal Credit and the Low Pay Commission. Each of these offer a platform where Labour must seize the opportunity to announce transformative policies.