19 May 2022

Food Prices Tracking: May Update

Overall inflation has jumped to the highest level in 40 years

Shocking figures out this week show that overall inflation has jumped drastically to 9% in the 12 months to April 2022, up from 7% in the 12 months to March 2022, reaching the highest level since March 19821.

This month’s increase is in large part driven by fuel price increases off the back of the 54% increase in the energy price cap (the maximum amount energy companies can charge an average customer) that came into effect at the start of April.

Estimates are that inflation will remain high (although could drop slightly over the next couple months before rising again), and will likely see another big increase when the next energy cap increase is implemented in October2 with predictions the cap could increase by a further £6003.

Food prices continue to rise in the face of global and domestic issues around food shortages and input costs

This week the Bank of England described the situation with food prices as “apocalyptic”4. Latest Government figures released on Wednesday show that take-home retail prices for commonly purchased food and drink items have risen by 6.7% in the 12 months to April 2022, up from 5.9% in the 12 months to March 2022 (Source: Consumer Price Index (CPI), Office for National Statistics).

The public are feeling this impact as shown by an ONS survey finding that 92% of people reported their grocery bill has increased, and 39% of adults are cutting back on their grocery shop (a 15% increase in just a fortnight)4.

A large increase in out of home food prices has also been seen due to the VAT rate for hospitality returning to 20% in April from 12.5% (it was temporarily lowered to help businesses recover from decreased business during the Covid-19 pandemic)5.

Food price inflation continues to be driven by disruption to the global food market following the invasion of Ukraine, on top of the pre-existing issues caused by Covid, Brexit and longer-term issues such as climate change, all impacting on the price of food and inputs (such as fuel, fertiliser and labour) (see previous blogs in series for further details).

Global wheat price increases resulting from Ukraine being unable to export and harvest wheat are now being further pressurised by India (the second largest producer of wheat) banning wheat exports following a heatwave impacting on crops6. Poor harvests of rapeseed and soya bean for oil has also faced climate-related disruption to harvests exacerbating the global cooking oil shortages from lack of exports from Ukraine and Russia7. As it currently stands, the FAO report that the war will mean that 20-30% of the farmland in Ukraine will not be planted or harvested this year8 but the longer the war in Ukraine continues, the greater the impact will be on global food prices.

Concerns regarding food production in the UK are also rising. The extreme increase in fertiliser prices (with some reports of a five fold increase9) are causing farmers to buy less fertiliser which could decrease yields. Furthermore, the EFRA committee has warned that the chronic labour shortage could increase prices and could make us more dependent on imports10.

Shocking numbers of people are being left unable to cope with rising prices

The ongoing cost of living crisis is making food increasingly unaffordable, due directly to rising food prices, indirectly to pressures on disposable income from increasing prices in other areas (most notably energy), and incomes not keeping up with the rapidly increasing levels of inflation (see previous blogs for further details).

The poorest households spend a higher proportion of their income on food and energy and so are impacted more by any increase in prices. IFS analysis shows the unequal effect of inflation for people on the lowest income with the poorest tenth of households facing inflation of 10.9% compared to the richest at 7.9%11.

The devastating impact rising prices are having a on people’s ability to afford food was clearly demonstrated in data released by The Food Foundation last week showing a 57% increase in food insecurity levels since January, now affecting an appalling 7.3 million adults and 2.6 million children (Food Insecurity Tracker).

This raises substantial concerns for people’s physical health as they have to turn to lower nutritional quality food because it is generally cheaper, and the impact on their mental health as they cope with the stress of being unable to afford the essentials. A recent survey by the Royal College of Physicians found 55% of Brits reported their health has been negatively impacted by the cost of living crisis (a quarter of them reported they had also been told that by a medical professional). Of those, 78% said it was due to rising cost of food12.

Fuel prices are also continuing to impact on people’s food budgets and intake. Food banks are reporting being asked to provide food that doesn’t require cooking as people can’t afford to pay for the energy for a fridge/freezer or cooking costs13. Citizen’s Advice are warning that some prepay customers have stopped topping up their metres and are trying to get by without energy14. Approximately 4.5 million households in the UK have prepayment meters, many of whom are on low incomes and ironically, the increase in the energy price cap was higher for them than people on direct debits.

Not only have energy bills risen but so have rents: the average rent is now £88 per month more expensive than at the start of the pandemic putting further pressure on incomes15. Furthermore, ONS data shows that real wages have decreased by 1.9% in a year16. According to NIEST, 1.5 million households across the UK face food and energy bills greater than their disposable income in 2022-2317.

Politicians’ misinformed comments and actions show a disturbing lack of understanding of the impact of the cost-of-living crisis being faced by the public

Various comments from politicians over the past month on how to cope with the cost of living crisis have been somewhat out of touch. Lee Anderson MP sparked outrage amongst many when he offered the view that cooking and budget skills were all that was needed to remove the need for food banks (see here for our response demonstrating that the evidence does not support his statements). George Eustice MP suggested people should try switching to budget ranges18, with no consideration for the fact that a large proportion of the population were already dependent on the cheaper budget ranges to buy the food they need before the recent increases and there is no cheaper option for them to switch to now. Rachel MacLean MP suggested that people should just work longer hours or find better paid jobs19 showing a total lack of regard for all the people working multiple jobs and long hours in jobs where the pay is too low due to the Government’s “living wage” being set at a level which is not sufficient level for people to live off.

The measures that were announced in the Spring Statement by the Chancellor were barely enough to make a dent in the problem for low-income households. Reportedly the Government withheld giving more financial support thinking that households could rely on savings20, despite problems with people going into debt and having to use up savings to cope with the financial impact of the pandemic being widely reported. The Chancellor committed to rebates on council tax of £150 for some households from April but reports are emerging that these rebates have not yet reached many in need21. The NEA report this is because many of the poorest households do not pay council tax by direct debit.

A glimmer of hope came in the form of the announcement that Local Authorities would be provided with further funding towards the Household Support Fund to support those on the most at risk. However, Freedom of Information requests show that the previous round of the Household Support Fund (provided to Local Authorities last autumn to help poorer households with essentials for six months over the winter) ran out at least a month too early in one in six local authorities and some running out after just three months22. This Fund needs to be higher to meet the level of demand and needs a long term commitment so local authorities can plan appropriately.

The Government’s decision this week to abandon policy that has been passed through parliament to ban multi-buy promotions (e.g. buy one get one free offers) on unhealthy food was yet another failure to understand the cost of living crisis. The evidence indicates that these offers result in people spending more than they otherwise would (see here for our full response).

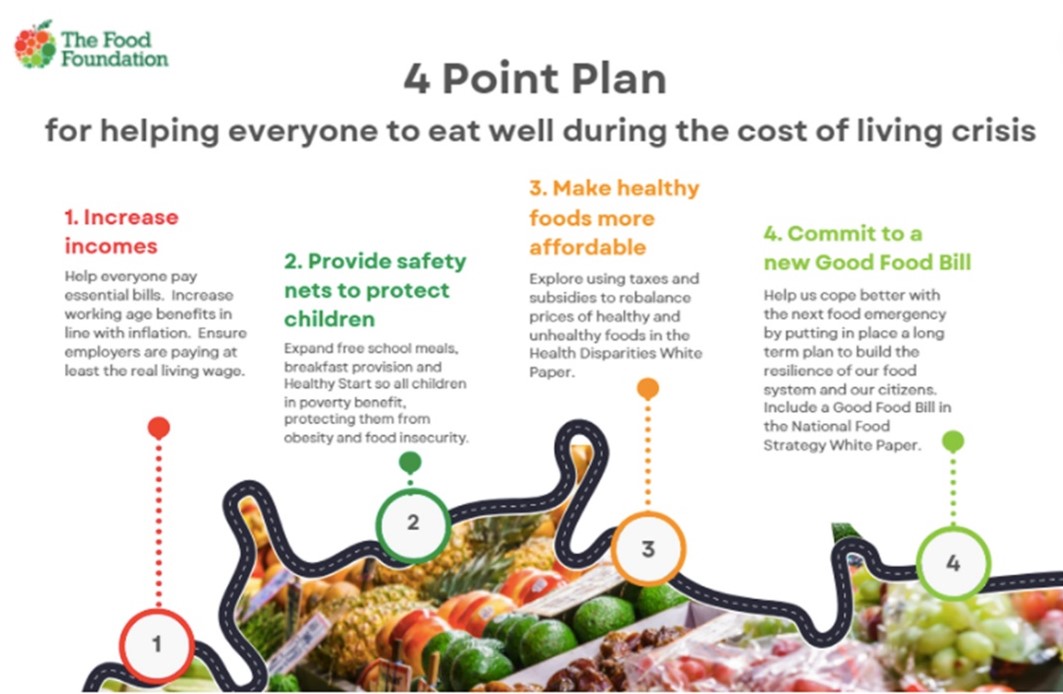

The startling failure of Government to grasp the severity of the situation means that families across the country are heartbreakingly left to struggle. The Food Foundation’s four-point plan sets out the actions that Government should be taking to effectively tackle the problem and ensure everyone can afford to eat well through this cost-of-living crisis, starting with ensuring sufficient incomes through benefits and wages:

Shona joined The Food Foundation as a Project Officer in 2019 and has worked on research, policy and advocacy across a range of projects over that time including leading our food insecurity surveys and flagship annual Broken Plate reports. She now works across the charity's policy portfolio including our children's food campaigns, food insecurity and food environments. She is a Registered Associate Nutritionist with a background in clinical nutrition who worked in dietetic departments in NHS hospitals before joining The Food Foundation.

Indu joined The Food Foundation in 2019 as part of the Rank Foundation’s Time to Shine scheme, moving into a Project Officer role in 2020. She works on the Peas Please and Plating up Progress projects. Prior to joining The Food Foundation, Indu completed a MSc in Public Health and a BSc in Human Nutrition. She is interested in reducing health inequalities, children’s health and wellbeing, and sustainable and nutritious food system/diets. Indu is also a lover of veg, having recently taken up urban gardening.